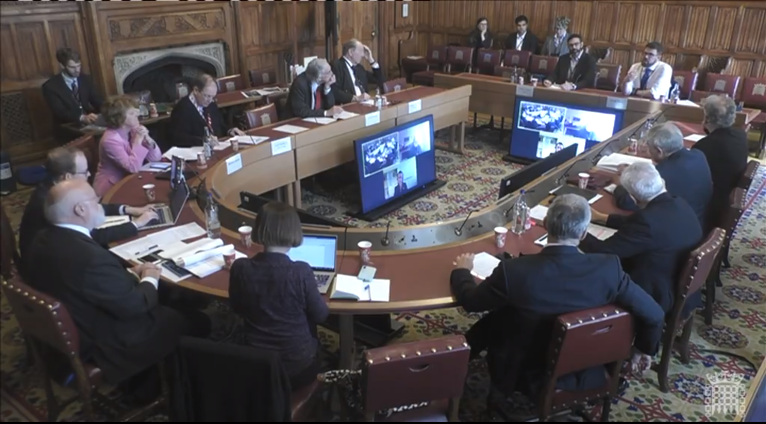

First evidence session. Click to watch video

This article was originally published on Drone Wars.

Author: Peter Burst

A special investigation set up by the House of Lords is now taking evidence on the development, use and regulation of artificial intelligence (AI) in weapon systems. Chaired by crossbench peer Lord Lisvane, a former Clerk of the House of Commons, a stand-alone Select Committee is considering the utility and risks arising from military uses of AI.

The committee is seeking written evidence from members of the public and interested parties, and recently conducted the first of its oral evidence sessions. Three specialists in international law, Noam Lubell of the University of Essex, Georgia Hinds, Legal Advisor at International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), and Daragh Murray of Queen Mary University of London, answered a variety of questions about whether autonomous weapon systems might be able to comply with international law and how they could be controlled at the international level.

One of the more interesting issues raised during the discussion was the point that, regardless of military uses, AI has the potential to wreak a broad range of harms across society, and there is a need to address this concern rather than racing on blindly with the development and roll-out of ever more powerful AI systems. This is a matter which is beginning to attract wider attention. Last month the Future of Life Institute published an open letter calling for all AI labs to immediately pause the training of AI systems more powerful than GPT-4 for at least six months. Over 30,000 researchers and tech sector workers have signed the letter to date, including Stuart Russell, Steve Wozniak, Elon Musk, and Yuval Noah Harari.

Leaving aside whether six months could be long enough to resolve issues around AI safety, there is an important question to be answered here. There are already numerous examples of cases where existing computerised and AI systems have caused harm, regardless of what the future might hold. Why, then, are we racing forward in this field? Has the combination of tech multinationals and unrestrained capitalism become such an unstoppable juggernaut that humanity is literally no longer able to control where the forces we have created are taking us? If not, then why won’t governments intervene to put the brakes on the development and use of AI, and what interests are they actually working to protect? This is unlikely to be a line of inquiry the Lords Committee will be pursuing.

Humans vs Computers

Covering rather different ground, Lord Fairfax asked a question raising the common misconception that computers, which lack human emotions and frailties and make decisions purely on the basis of information, might be able to make ‘better’ decisions on the battlefield than human soldiers. In response Georgia Hinds was able to unpick this myth, regularly put forward by apologists for the arms industry. Such scenarios are based on an number of assumptions – entirely unbacked by any empirical evidence – and compare a worst-case decision made by a human with a best-case decision made by a computer. While it is indeed true that a machine will not be subject to the emotions of rage or revenge or the demands of fatigue, unlike a machine a human is responsible for their actions and can be held to account for any wrongdoing.

Although automation in weapon systems may give rise to a number of benefits for the military – principally speed of response – these should not be confused with improvements in compliance with the international humanitarian law which governs warfare. In fact, speed poses a significant risk in this respect. A machine may be reliable at identifying a particular target profile, but this does not mean that the profile it has identified represents a legitimate target, or that it will be able to destroy it with precision. If an automated weapon system operates too fast there may be no opportunity for a human to monitor it or, if things go wrong, intervene to prevent an unlawful or unnecessary attack.

If we don’t do it…

Another commonly made argument was dragged out by Lord Hamilton, who was concerned that enemies such as Vladimir Putin would not concern themselves with the ethical and legal issues relating to new weapons technologies, and that the UK should therefore develop the same technologies so as not to be at a military disadvantage against these enemies. This hoary old chestnut can be, and usually is, used to justify any dubious practice in international affairs and is basically an argument against any kind of legal constraint, because it’s always possible to argue that there will be someone who might break the law.

If the UK really is on a different ethical par that Putin’s Russia as it regularly argues, then such arguments have no relevance. As witnesses explained, nations act ethically and legally because that is the kind of country they want to be and the standards they set for themselves. Such ethical and legal compliance is not based on reciprocity – something we only do when others also act that way – but are our agreed standard way of acting, a set of norms for conduct and sanctions for offenders, which provide stronger collective protection than voluntary constrains which individual states may make. The majority of states currently support a legally binding international instrument to control autonomous weapon systems, and the UK should do likewise.

From a pragmatic viewpoint, there is no advantage to any nation in entering into a high-tech arms race, particularly so for nations like Russia which lag behind the US in their technological expertise. There is no reason to believe that Russia is less inclined to comply with international humanitarian laws, which provide protections to its own soldiers and civilians, than other nations. Russia has committed war crimes during its invasion of Ukraine – for which those responsible should be held to account – but, regrettably, so too did Western nations during the Kosovo war and the invasion of Iraq.

–//–

The Lords committee will be taking further evidence over the weeks ahead, with witnesses discussing how the development of autonomous weapons might impact the UK’s foreign policy and its position on the global stage during the second oral evidence session, and representatives from the military tech sector scheduled to give evidence at a session planned for 20 April. We will be providing comment on these further sessions in due course.